Flesh Made Wood: The Invention of Artificial Refrigeration

Refrigeration’s ability to transform bodies (and lifestyles) has made it an abiding symbol of modernity. Life Magazine, November 19, 1965

The refrigerator is among the most familiar of household appliances. It may also be a distinctively American machine: it has long figured in the domestic sphere as a symbol of prosperity. More recently, it has become a source of ecological guilt at a moment of increasing climate anxiety.

Above all, refrigerators are a ubiquitous and unremarkable fact of contemporary life, not only in North America but throughout the developed world. For the first generation to observe the power of mechanical refrigeration, however, the new technology was anything but mundane. The potential of artificial refrigeration inspired grandiose visions of all kinds, and the power of the technology—its ability to arrest decay, to produce a change of state even if only in a humble leg of lamb or slab of butter—seemed to place humankind in a new relationship of mastery over the natural world itself.

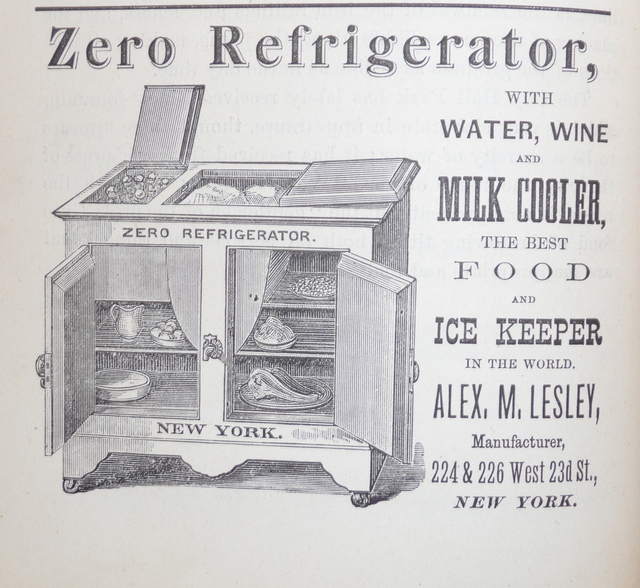

Preserving foodstuffs by mechanical refrigeration became an industrial possibility only in the 1870s and 1880s. The key innovation was a particular kind of heat pump that, when attached to an insulated chamber, could maintain its temperature at or below freezing for very long periods of time. Prior to this, a vast and lucrative trade in natural ice had fueled the preservative industry. The scale of this trade was enormous. In the 1860s, the process of “storing the winter,” as historian William Cronon has described it, linked the lakes of Wisconsin and Massachusetts to places as distant as colonial India, and butchered meat departing the great stockyards of Chicago rode the rails in “ice box[es] on wheels.”

Cold: A New Manufacture, a pamphlet produced in 1878 by the Pure Ice Manufacturing Company, Ltd. The author

But although the use of natural ice for refrigeration produced many of the same effects as mechanical refrigeration, it remained reliant on the cycle of the seasons, and was therefore susceptible to the whim and will of Mother Nature. For interested parties—pastoralists, ranchers, agriculturalists, industrialists—it was not so much the unreliability of winter that hampered their plans, but the un-pliability of the natural world. Ice moved to the cyclical rhythm of the seasons, ebbing and flowing with the passage of winter into spring, while nineteenth-century entrepreneurs sought a way to preserve perishable substances that would instead be susceptible to the constant rhythm of capital: a steady beat set to the metronome of stock exchanges, markets, supply and demand.

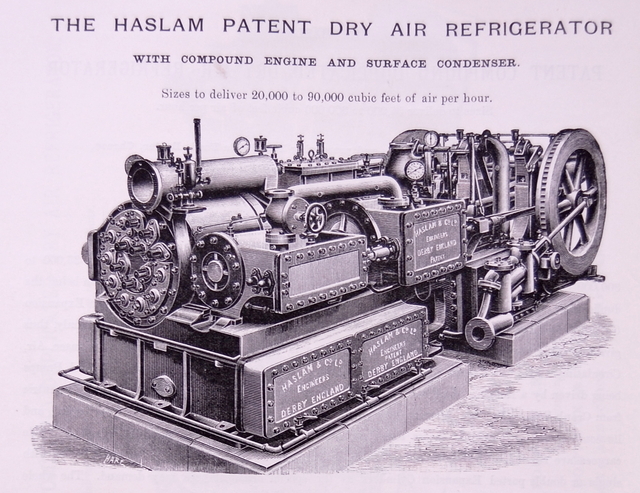

A coal-powered engine that circulated ether, ammonia, or even plain water, alternately expanding and contracting it, and thereby inducing repeated changes of state from liquid to gas and back again was independent of anything other than its energy input. It relied only on a regular supply of fuel and human ingenuity—two things that Victorians believed they had in abundance. Copper piping and cork or paper insulation allowed these machines to lower the temperature of a confined space such as a storehouse or ship’s hold, and to and maintain it at or below freezing almost indefinitely.

A Haslam Patent Dry Air Refrigerator, from the Illustrated Catalogue of Ice Making and Refrigerating Machinery (1893). Derbyshire Public Records Office

The development of this technology was a transnational phenomenon. Engineers in Scotland, America, Australia, Europe, and of course in Mother Britain, all patented their innovations over the course of the nineteenth century. Between 1855 and 1876, for example, 128 patents for mechanical refrigeration were taken out in Great Britain alone. One of the first successful oceanic shipments of frozen meat sailed from Buenos Aires to France in 1877.

But for British colonists in Australia and New Zealand, this new technology was particularly exciting. Long known for their vast populations of sheep, by the 1850s and 1860s both Australia and New Zealand appeared to be suffering from an incredible oversupply of sheep and lambs. These animals produced abundant wool for export, but their carcasses presented a logistical problem. The journey to Great Britain was much too long to send live sheep without them losing weight (thereby cutting into the profits to be had), even though Britons at mid-century faced shortages of animal protein amounting to what they considered a “meat famine.”

Colonial populations, on the other hand, were nowhere near the size required to absorb the surplus meat produced by the region’s wool economy: sheep outnumbered people twenty-five to one in Australia, and twenty-seven to one in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s. Refrigeration, with its ability to forestall decay and to maintain bodies “in a state of what one may call suspended animation,” offered a seemingly perfect solution to this transhemispheric problem of supply and demand. By the 1890s a thriving trade in frozen meat from the antipodes to metropolitan Britain had emerged. “Climate, seasons, plenty, scarcity, [and] distance…all [shook] hands” in this new trade, as an early Australian pioneer in the trade, Thomas Mort, had predicted in 1875, and out of this temporal and geographical reconfiguration came “enough for all.”

This great handshake had profound implications for global supply chains. Feedlots, the use of growth hormones in the cattle industry, and the carbon footprint of industrial animal agriculture are among the large-scale consequences of this historical transition. But the change of state that mechanical refrigeration induced at the scale of fleshly bodies themselves was no less astonishing for contemporary observers. Before frozen peas and TV dinners were commonplace, journalists who first encountered the frozen bounty of the antipodes could hardly refrain from striking it, simply to hear its frozen ring. A journalist visiting the recently-arrived Australian ship S.S. Orient in Gravesend on the Thames in 1881 reported its cargo “was firm as a rock, and gave out a sharp sound when struck,” while a colonial counterpart reported of New Zealand’s inaugural cargo of frozen mutton that the carcasses were “as hard as boards, and emit, when tapped with a stick, the sound of an empty barrel.”

Artificial refrigeration, it seemed, effected technological transubstantiation—a change of state to match that which powered the engines themselves. In reducing things to “such a state of frigidity,” flesh was made wood or rock—sometimes even metal. A technological wonder, indeed.

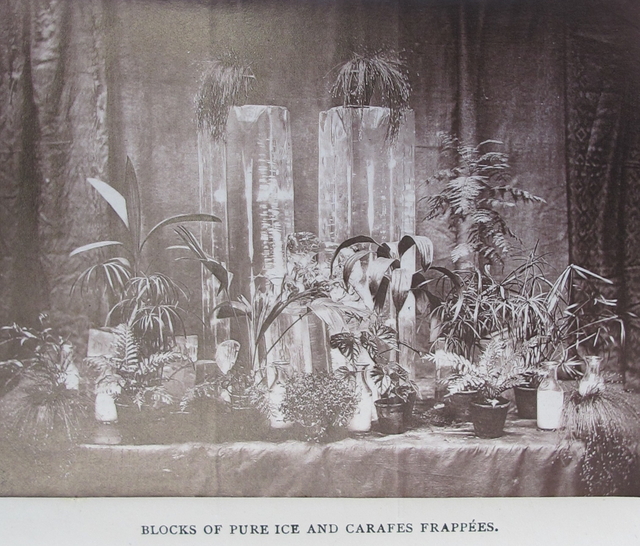

The 1878 pamphlet Cold: A New Manufacture featured a number of staged photographs of ice blocks luxuriating in stylish settings. The author

Of course, Victorian Britons weren’t completely naive when it came to the effects of extreme cold on flesh, live or dead. The development of artificial refrigeration followed close on the heels of the Little Ice Age. In winter, the Thames froze regularly, and Britons from Manchester to London could expect to be substantially dusted by snow, if not engulfed in it. People knew what frozen looked and felt and sounded like, if not necessarily from direct experience, then at the very least in literary form. Reports and travel narratives from Canada, Russia and the Arctic exposed a voracious reading public to the experience of seriously low temperatures.

Yet the novelty of producing that state through mechanical means allowed for juxtaposing the very hot and very cold in hitherto unimagined ways. Passengers on ships equipped with refrigerated chambers could now enjoy cold butter while steaming through the tropics, and for a “comparatively small outlay after the first cost” of investing in a refrigerating engine, “one might be transported into ‘thrilling regions of thick-ribbed ice’ even in the midst of summer,” as one booster for the new technology enthused. Artificial refrigeration effected not only technological transubstantiation, it was also capable of putting the extremes of summer and winter cheek by jowl.

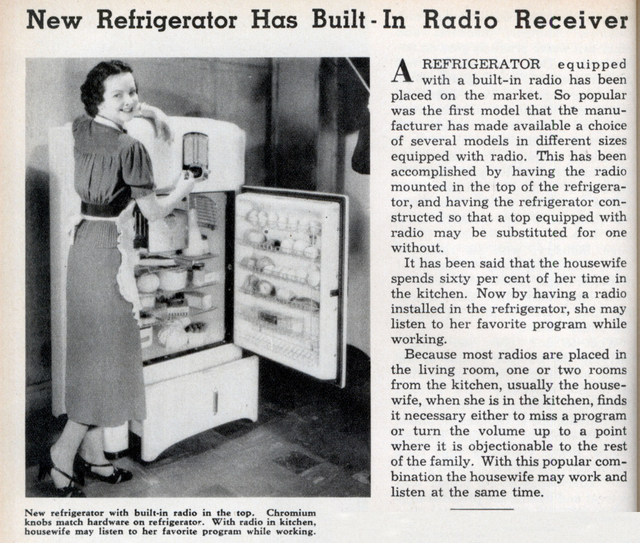

The twentieth century brought another wave of technological advances to refrigeration, like this report from the August, 1937 issue of Modern Mechanix that anticipated the “internet of things.” http://blog.modernmechanix.com

Refrigeration promised to free humanity from the confines of the natural world—to establish a mastery over nature that was part and parcel of imperial Britain’s larger self-identity on the world stage. Where the example of the Arctic had once provided a natural metaphor for the processes of mechanical refrigeration, by 1882 the metaphor had been inverted. There, in the coldest parts of the world, Nature performed “the work of a refrigerating machine.” Such was the power of artificial refrigeration to produce “icehouse[s] of the chemist’s fashioning, completely under man’s control,” that flesh was made wood, and nature came to resemble artifice.